Patient Presentation

A 5-year-old male came to clinic with a history of ~ 7 days where he would have emesis. The episodes occurred at random times usually at least 1 or more hours after he had eaten. He denied nausea and was still hungry but he would not eat as much as usual. The emesis did not have blood or mucous and was of the food and beverages he had consumed. Some of the food was ingested 12-18 hours previously. The episodes occurred twice a day at least and at any time of the day. They usually did not occur over night, but parents said that one time he had an episode about 5 AM in the morning. They were not sure if he was already awakened and then had emesis or if he was awoken by it. He did have some abdominal pain especially around the time of the emesis but was able to play normally. They also noted that his abdomen seemed to be slightly larger. He had normal urination but his bowel movements were less frequent. He still was having a normal soft stool at least daily to every other day without diarrhea. He denied any bad tastes in the back of his throat other than when he had emesis. The family denied any self-gagging behaviors and had a common variety of over-the-counter medications in the home. They also denied any social stressors, recent illnesses, trauma or foreign body ingestions. The past medical history revealed a healthy male with some minor illness and no surgeries. He had been a “spitty” baby, but had not had gastrointestinal problems since. The family history was positive for gastroesophageal reflux disease in a maternal aunt. The review of systems was negative including no fever or rashes.

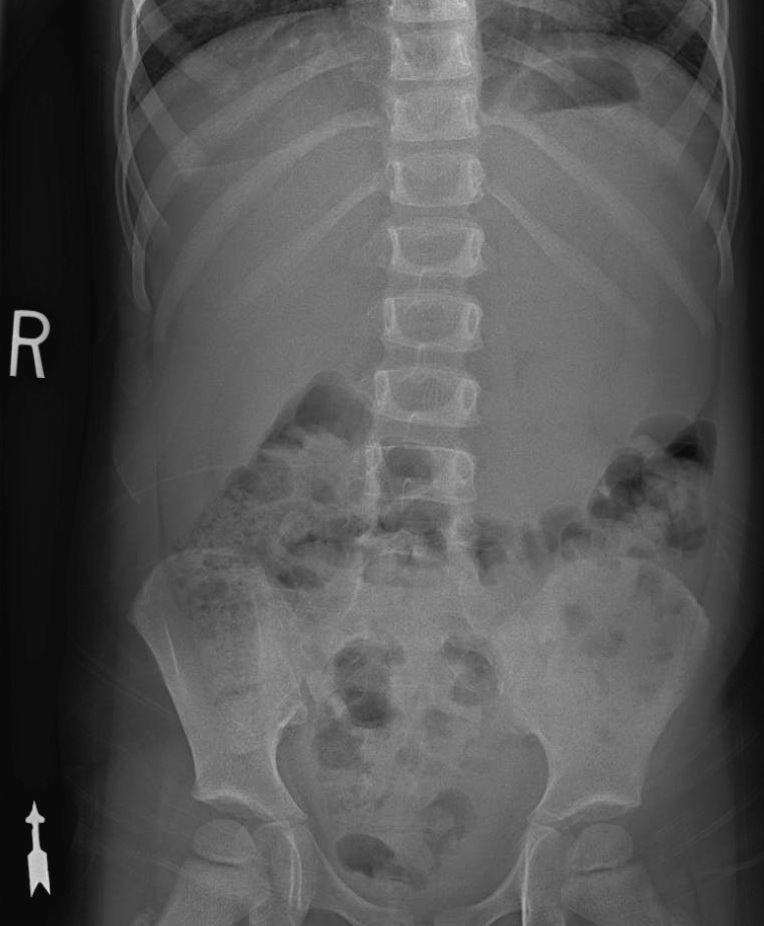

The pertinent physical exam showed a thin male in no distress. Vital signs were normal. His weight was 10% and was down 250 grams from a weight earlier in the month. His height was 25-50%. HEENT including his teeth, heart and lungs were normal. His abdomen was slightly enlarged overall with increased tympani with percussion. Bowel sounds appeared normal in all quadrants. There was no specific tenderness and no hepatosplenomegaly. The left upper quadrant seemed “fuller” on palpation but no specific mass was palpated. His genitourinary examination was normal as was his neurological examination. His hands did not show any bite marks. The diagnosis of emesis without an obvious cause was made. The work-up included a complete blood count, electrolytes, BUN, creatinine and urinalysis that were all negative. The radiologic evaluation of an abdominal radiograph showed an enlarged fluid filled stomach displacing the transverse colon inferiorly.

The diagnosis of gastroparesis was made. A pediatric gastroenterologist was consulted by telephone and thought that it was most likely due to a virus that was not recognized and the patient was started on erythromycin for its prokinetic effects. The patient was scheduled for an upper gastrointestinal examination to rule out other potential causes of the emesis 5 days later that was normal. On followup at 10 days after treatment initiation, the history showed that the patient had had a slow diminution in the emesis that had completely stopped 3 days previously. He occasionally would still complain of abdominal pain and occasional bloating but his parents felt this was also decreasing. At his health supervision visit 2 weeks later his parents said that all the symptoms had resolved at least 1 week previously.

Figure 109 – Upright abdominal radiograph shows an air fluid level in the fundus of an enlarged fluid filled stomach that is displacing the transverse colon inferiorly.

Discussion

“[Gastroparesis] (GP) is a motor and sensory disorder of the stomach characterized by delayed gastric emptying in the absence of mechanical obstruction. Symptoms classically include nausea, vomiting, early satiety, bloating, postprandial fullness, abdominal pain and weight loss….GP is often not recognized and thus can remain untreated in children.”

In the adult population, the age adjusted prevalence of GP is 9.6 (for men) and 37.8 (for women) per 100,000. There is no specific prevalence data available for children. It appears from some data that GP identification is rising and some data suggests that this is not due to increased incidence but due to increased awareness of the problem and more accurate classification.

In one study, girls presented later than boys (9 versus 6.7 years), vomiting and abdominal pain occurred in more than 50% of patients and the delayed stomach emptying was more often characterized as mild.

The most common causes in this study were idiopathic (70%), drugs (18%) and post-surgical (12.5) and post-viral (5%). In another study post-viral GP accounted for 18% of cases. It is possible that the some of the idiopathic cases are actually post-viral, and some sources quote idiopathic and post-viral as the two most common causes of gastroparesis in children.

Treatment often include dietary changes (such as decreasing dietary fat or consuming lactose-free diets, having small frequent meals) and medications and rarely surgery.

Medications include proton pump inhibitors and promotility agents (such as tegaserod, metoclopramide and erythromycin).

Learning Point

The good news about gastroparesis is that most patients resolve within weeks to a few months. In one study of the outcome of GP, “…the overall rate of symptom resolution was 52%, which was achieved at a median of 14 months from the time of diagnosis. In those patients in whom symptoms ultimately resolved, 84% did so by 12 months and all resolved by 36 months.”

Factors associated with symptom resolution included younger age (infants > children > adolescents) male, postviral gastroenteritis, short duration of symptoms and response to prokinetic agents.

Questions for Further Discussion

1. What is in the differential diagnosis of emesis?

2. When should a gastric-emptying study be considered for possible gastroparesis?

Related Cases

- Disease: Gastroparesis | Stomach Disorders

- Symptom/Presentation: Abdominal Pain | Vomiting

- Age: School Ager

To Learn More

To view pediatric review articles on this topic from the past year check PubMed.

Evidence-based medicine information on this topic can be found at SearchingPediatrics.com, the National Guideline Clearinghouse and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

Information prescriptions for patients can be found at MedlinePlus for this topic: Stomach Disorders

To view current news articles on this topic check Google News.

To view images related to this topic check Google Images.

To view videos related to this topic check YouTube Videos.

Rodriguez L, Irani K, Jiang H, Goldstein AM. Clinical presentation, response to therapy, and outcome of gastroparesis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012 Aug;55(2):185-90.

Waseem S, Islam S, Kahn G, Moshiree B, Talley NJ. Spectrum of gastroparesis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012 Aug;55(2):166-72.

Nusrat S, Bielefeldt K. Gastroparesis on the rise: incidence vs awareness? Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013 Jan;25(1):16-22.

ACGME Competencies Highlighted by Case

1. When interacting with patients and their families, the health care professional communicates effectively and demonstrates caring and respectful behaviors.

2. Essential and accurate information about the patients’ is gathered.

3. Informed decisions about diagnostic and therapeutic interventions based on patient information and preferences, up-to-date scientific evidence, and clinical judgment is made.

4. Patient management plans are developed and carried out.

7. All medical and invasive procedures considered essential for the area of practice are competently performed.

8. Health care services aimed at preventing health problems or maintaining health are provided.

9. Patient-focused care is provided by working with health care professionals, including those from other disciplines.

10. An investigatory and analytic thinking approach to the clinical situation is demonstrated.

11. Basic and clinically supportive sciences appropriate to their discipline are known and applied.

13. Information about other populations of patients, especially the larger population from which this patient is drawn, is obtained and used.

23. Differing types of medical practice and delivery systems including methods of controlling health care costs and allocating resources are known.

24. Cost-effective health care and resource allocation that does not compromise quality of care is practiced.

Author

Donna M. D’Alessandro, MD

Professor of Pediatrics, University of Iowa Children’s Hospital